To understand why a company called ViSalus is the fastest-growing company of its size in the United States, just watch co-founder Nick Sarnicola in action at one of the company’s periodic sales conferences.

In the video that ViSalus posted on YouTube of a July conference in Miami, Sarnicola’s turbocharged pitch inside a packed 18,000-seat arena has people on their feet, pumping fists, clapping, waving, even dancing. A politician or entertainer can only dream of an audience response like this.

People don’t usually pay good money to travel to Miami in sweltering summer heat and then readily wedge themselves into a packed arena to see someone strut around and talk on a hastily assembled theatrical stage — about a company whose major product is powder for a weight-loss shake.

Sarnicola is an unlikely standard-bearer. He has no real college training in health care or any related field; briefly he was a salesman for a collapsed telecom company. Though he is the author of an evangelistic tome about becoming rich by age 25, he was evicted just a few years shy of that for not paying his apartment’s rent.

To this audience, however, Sarnicola is a superstar. No one sells more products for ViSalus; the sales group he and his wife founded is responsible for 75 percent of its revenue.

Rich, good-looking and with an attractive spouse, Sarnicola is proof to the throng that through ceaseless effort and unyielding commitment, they too can live a glamorous lifestyle like he does.

Called a “global ambassador,” a sales rank only he and his wife hold, Sarnicola did not deliver his Miami speech to impart hard-won sales tips. He was giving a sermon designed to morally validate a congregation where salvation is found through selling ViSalus’ weight-loss and nutrition products to networks of their friends, relatives, neighbors and colleagues.

ViSalus is a multilevel marketing company that promises ordinary folks a shot at financial success based solely on their skill at building a sales group that essentially draws on personal social circles: A distributor must recruit customers (usually starting with friends, neighbors, relatives) who are asked to enroll still others as customers, who are then encouraged to bring in more new members to the sales group.

The Miami sales conference was designed to reinforce the secular theology of economic independence and self-help advocated by ViSalus — and other multilevel marketing enterprises. For 60 years, such companies have used their sales gatherings to dangle the prospect of a path away from corporate drudgery or limited means.

During Sarnicola’s dramatic closing speech in Miami, where surrounded by fellow ViSalus cofounders Blake Mallen and Ryan Blair, he embarked on a riff reminiscent of a thousand 12-step meetings and evangelical pulpits: He confessed his imperfection and weaknesses, pledging an authentic and single-minded focus to help them in the hunt for health and prosperity.

Every multilevel marketing firm, including industry leaders like Nu Skin, Herbalife and Amway, relies on a variation of this appeal. Most multilevel marketing presentations contain so much language about independence that they could be backdrops for a small town’s Fourth of July celebration. But ViSalus has a different, thoroughly modern approach.

ViSalus wants its freelance distributors to party like rock stars and look like models. While Amway appeals to the Norman Rockwell-like sensibilities of faith, country and community, ViSalus is in your face, bringing in wrestlers like Hulk Hogan and rappers such as Master P and Lil Romeo to pitch its products.

So not only does Sarnicola’s somewhat erratic personal background fail to detract from his appeal with members of his adoring audience; it’s proof that their own imperfections can be forgiven. If they buy into the philosophy and sell like mad, they, too, can live in a Miami beachfront penthouse like Sarnicola, fly in a corporate jet like Mallen or build a home in the Hollywood Hills like Blair. ViSalus, in other words, is a corporate version of the French Foreign Legion, where one’s past is forgotten as long as the present is dedicated to the cause.

What the thousands of applauding people in that Miami arena and the other halls and hotel ballrooms ViSalus fills for its confabs are dedicating themselves to, however, has every indication of being a classic pyramid scheme.

Sarnicola, Mallen and Blair are making off like bandits, living precisely the type of life they claim can be had through a total commitment to ViSalus. Yet its corporate filings tell a very different story: Despite plenty of hard work and expense — which often end up being much more than the company lets on — ViSalus’ army of believers are probably in for a big letdown.

Those flocking to the arenas and ballrooms are likely to be fleeced as ViSalus’ management team and corporate owners reap the rewards of a remarkably effective promotional and marketing effort fronted by Sarnicola. (And while most multilevel marketing executives run from any mention of the word pyramid, ViSalus embraces it. Indeed Sarnicola, his wife and a few others recently even created their own online reality show about ViSalus sales, which they brazenly titled “That Pyramid Thing.”)

There’s nothing new about the risks of losing gobs of money and time in a pyramid scheme: Voluminous research has documented the astronomical failure and dropout rates of participants in dozens of multilevel marketing companies. Seen in a cold light, ViSalus is just another fast-growing player in a field that has seen dozens rapidly emerge, only to fade quickly.

What makes ViSalus stand out is its highly unusual relationship with its corporate parent, Blyth, a publicly traded marketing and catalog company based in Greenwich, Conn. Blyth owns most of ViSalus and has come to depend on the subsidiary’s rapid growth to sustain it.

And that’s a very big risk for Blyth’s investors. Because as ViSalus’ fortunes fall to Earth, Blyth will undoubtedly fall much further and much faster.

ViSalus mixes it up

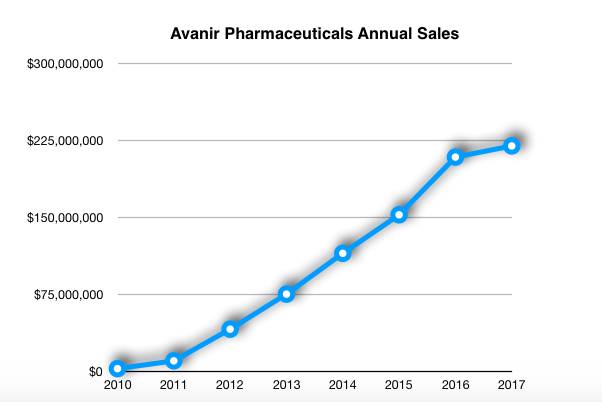

In the pantheon of Michigan companies, ViSalus doesn’t quite command the level of brand awareness that Ford, General Motors or even Domino’s Pizza enjoy, but those companies would surely love to have a fraction of the growth rate registered by ViSalus. In a recent filing, sales figures for ViSalus’ main product, a powdered meal-replacement shake that is part of a 90-day weight loss and marketing initiative it calls Body by Vi, suggest annual growth so massive that Americans appear to be skipping meals with ViSalus shakes in the same numbers that they download music through iTunes.

For the first half of this year, ViSalus’ weight-management unit logged a 482 percent rate of growth, compared with the first half of last year. It wasn’t just that one unit either that had spectacular results; the entire company’s sales mushroomed 451 percent over the same period.

ViSalus took in $327.3 million in sales this year through June 30, with about $222 million of that derived from its weight-management unit. As any analyst knows, it’s vastly more difficult to realize a spike in growth rate of that magnitude when the sales numbers are in that range.

The sales figures seem to indicate that the ViSalus shake mix isn’t just a popular product but that a paradigm shift in American behavior is under way.

The Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation tried to find any company with a remotely comparable growth rate. We searched publicly traded companies also headquartered in the United States and with at least $1 million in annual revenue and a compound yearly growth rate of 300 percent. (The search excluded companies in the pharmaceutical, biotech and energy exploration and development sectors whose fortunes hinge on external factors like regulatory approvals and geopolitics.)

The result: Among companies of its size, ViSalus stands alone in a category of one.

Plus, ViSalus is posting astronomical growth rates while operating as a multilevel marketing business. This is a hard road to travel: ViSalus competes against the established products and sales networks of multilevel marketing giants like Herbalife as well as the well-located niche retail stores like GNC’s and universally distributed brands like Slim-Fast with deep-pocketed corporate parents.

Having tons of established competition usually prompts a bitter price war in which only the fittest — and most ruthless — survive, not the shattering of sales records.

But that’s ViSalus in a nutshell: It seems to defy the laws of marketplace math.

At least that’s what its company executives want outsiders believe.

But some cracks in the carefully constructed veneer are already starting to show. An IPO for ViSalus announced in August was pulled in September because, as Blyth’s chief executive said in a conference call, ViSalus’ growth wasn’t being “properly valued.”

What a corporate statement like that probably means is that ViSalus’ bankers at Jefferies told Blyth no one was willing to pay the price being asked for the stock. (ViSalus CEO Ryan Blair hosted a chat on Facebook on Sept. 26 during which he claimed that it was his idea to cancel the IPO, Blyth management deserved credit for listening to him and that he was overjoyed. Blyth, in other words, spent $4.7 million in fees prepping an IPO of a subsidiary even though its CEO was dead set against it.)

When audited 450 percent growth rates can’t attract a proper bid from the same investor universe that happily gobbled up shares from Merrill Lynch, Fannie Mae and AIG in 2008, something has to be amiss.

A good place to start looking for the real reason the IPO was grounded is the prospectus filed by ViSalus’ holding company, FVA Ventures. In the columns of numbers and buried in the footnotes, a pattern emerges: Neither management skill nor the soundness of its products has anything to do with ViSalus’ record-breaking growth.

Blyth makes ‘folksy’ pay

The key to understanding what makes ViSalus tick is to know just how different it is from its corporate parent — and onetime rescuer — Blyth.

Founded in 1977 and cobbled together from half a dozen different candle, potpourri and gourmet food companies, Blyth has made money by dispensing with conventional wisdom. As much of the consumer business world has leaped onto various digital sales platforms, Blyth’s main business unit has persisted with its relatively folksy, old-fashioned method of enlisting sales consultants to host house parties where they sell candles and home fragrances to friends and acquaintances.

Don’t let the low-tech approach fool you, though; Blyth’s tactics have been every bit as effective as the slickest Madison Avenue marketing campaign. Research shows that in a slow economy consumers will hold off on a new car or fancier wardrobe, but when a neighbor five doors down whose daughter is on the same soccer team as yours invites your wife to a “product party,” there is a statistically excellent chance the checkbook will open for a few holiday-themed candles or gourmet jellies.

In recent years, many American businesses have undergone transformation in ways big and small, but Blyth didn’t seem to need to. As Amazon’s Kindle scotched interest in bookstores and Apple’s iPod killed stereo companies, people still continued to fork over $25 and $35 at a steady clip to have Blyth candles for the living room and den and potpourri for the downstairs bathroom.

Largely disengaged from the typical Wall Street promotional hype, Blyth takes its nondescript low-key approach to extremes, eschewing public relations and operating out of a modest office building in Greenwich, Conn. The company’s treasurer doubles as the investor relations representative. Even so, Blyth’s stock spent years above the $50 mark and Robert Goergen Sr., the former investment banker who founded Blyth, became seriously rich along the way. There have been richer and flashier CEOs, to be sure, but for investors who respected results, Goergen made betting against Blyth a dicey proposition.

That is, until 2008, when Blyth’s world came crashing down. The staggering decline in household discretionary spending, Blyth’s microeconomic lifeblood, was a knife directly aimed at its heart.

According to Blyth’s 10-K annual report, from 2010 to 2011, U.S. sales at its direct-selling PartyLite unit — traditionally the core of Blyth’s revenue — declined 22 percent and the number of independent consultants hawking products to the public fell 11 percent. Over the same span a year prior, sales at PartyLite’s U.S. operations plummeted 25 percent and the number of consultants dropped 17 percent.

There’s a grim playbook for management at publicly traded companies facing full-bore decline: radical cost-cutting, immediate asset sales and eventually a sale to a stronger competitor or bankruptcy.

Yet Blyth had an ace up its sleeve.

In August 2008, in a little-noticed move, Blyth bought a 43.6 percent stake in ViSalus, for $13 million. (Blyth later increased its ownership to 72.7 percent.) Perhaps Blyth’s thinking behind the investment resembled that of the veteran horseplayer who ignores the handicapper’s advice and on a hunch lays down $100 on the leggy long shot in the fourth race. The move paid off handsomely, and it seemed that for a while, ViSalus might have been one of the greatest investments in recent corporate history.

The year it inked the purchase agreement, Blyth recorded $1.16 billion in sales. Last year, factoring in ViSalus’ $230.1 million in sales, Blyth managed to post just $888.3 million in revenue. Without ViSalus, more than 50 percent of Blyth’s revenue since 2008 would have been gone, and to be frank, companies losing half their sales in less than five years usually exist only in the memories of the people who used to work there.

But unlike in horse racing, where the bet either pays or it doesn’t, the ViSalus acquisition was not a zero-sum game: Blyth got to live to fight another day, but it also committed to buy the final chunk of the company by the end of this year at a price that, because of ViSalus’ incredible growth, eventually became extraordinarily steep.

By this past summer, coughing up the sum of $271 million for ViSalus by the holidays seemed impossible for Blyth. (The final price Blyth pays could be $30 million higher, based on something ViSalus called the “Equity Incentive Plan,” allowing its distributors to get a cut of the purchase price.)

An IPO was an elegant solution for the company, allowing Blyth to sell a majority share of ViSalus, while retaining a minority stake and keeping control through the board of directors. Nonetheless, Blyth pulled the offering on Sept. 26, offering only a terse “market conditions” as the reason.

At Blyth, sporadic asset sales had taken place over the past four or so years but sinking home decor brands are not fetching many bids these days. Writing a check was out of the equation; Blyth had about $167 million in cash apart from ViSalus and once Moody’s Investors Service became aware of the company’s dire financial straits, it acted swiftly on Sept. 20 to change its outlook on the company to negative, closing the door on Blyth’s ability to borrow money below loan shark rates.

On Oct. 1, in a press release light on details, Blyth announced that its purchase of the final share of ViSalus would take place in April 2014 and that ViSalus’ founders agreed to have new employment contracts drawn up.

Blyth effectively took a cue from the U.S. government and pushed forward the day of fiscal reckoning 18 months. Management perhaps hopes that the shelved IPO can be relaunched when investors have forgotten what’s in the prospectus. The reality is that Blyth’s leadership bought a little more than a year and a half to devise Plan B. Regardless, even if consumer spending swells, it is difficult to imagine Blyth’s being able to generate enough cash to buy the remaining ViSalus stake.

A merger of opposites

The relationship between ViSalus and Blyth has its roots in a routine wireless Internet installation job in 2002 at a ranch in Santa Barbara, Calif. Over the course of the installation, the property owner, private equity veteran Frederick Warren, struck up a conversation with Ryan Blair, the chief of the company doing the job, SkyPipeline.

Outside of that chance meeting, a conversation between the two was perhaps unlikely. Warren is a well-established executive in the private equity and venture capital worlds, deeply involved with his alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania. In contrast, Blair had been a violent gang member in Los Angeles who had spent time in jail until his stepfather led him out of that life and interested him in business, as Blair explains at length in his book “Nothing to Lose, Everything to Gain.”

Blair’s wireless Internet service provider was a young company in search of cash, according to his book, and Warren, presumably always on the hunt for a new opportunity, was looking to better understand the possibilities in the wireless market.

Warren ultimately became convinced that Blair’s company had potential. He happened to be an outside adviser to Ropart Asset Management, a private equity fund owned and run by Robert Goergen Sr., the founder of Blyth. Warren suggested that Ropart invest in SkyPipeline and Ropart took the advice. In 2004 when NextWeb bought SkyPipeline for $25 million, both Blair and Ropart made out nicely.

The SkyPipeline sale gave Blair his first real money. At the time, Blair didn’t make such great decisions, as his book describes; he spent his windfall on a sports car and plenty of fun with girlfriends who had expensive tastes. Indeed one thing Blair omitted from the book designed to be a “warts and all” account of his entrepreneurial life, including peeks at his playboy lifestyle, is his declaration of a Chapter 7 bankruptcy in October 2005. His bankruptcy filing listed $125,000 in credit card debt and just $500 in assets; he was living in a Marina del Rey, Calif., condo leased by his stepfather. (ViSalus’ IPO prospectus does mention the bankruptcy.)

Still, in 2005 after Blair did a leveraged buyout to buy a company called ViSalus Science (later ViSalus) and needed some cash, he found a ready ear at Ropart. Blair retained the previous sales chief, Nick Sarnicola, and chief marketing officer, Blake Mallen, and in six months ViSalus’ sales grew 200 percent, according to Blair’s book. Traveling to Ropart’s Greenwich, Conn., offices, Blair met with Robert Goergen Sr. and his son Todd, the managing partner.

The pitch worked. Robert Goergen Sr. personally gave the go-ahead to invest $1.5 million in the ViSalus venture.

But there was a hook: Blair was prohibited from disclosing the role of the Goergen family or Blyth in the investment.

The anecdote suggests a recurring theme: the Ropart fund-Blyth Inc.-Goergen family nexus. Though Ropart and Blyth are two legally distinct entities, in practice they and the Goergen family form separate sides of one triangle, a mix of investments and personnel so fluid one needs a scorecard to track whose interests come first.

Then again, it was probably designed that way.

Consider this: Robert Goergen Sr., a former Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette banker and McKinsey partner, founded Blyth in 1976, serves as its chairman and CEO, and personally owns 30 percent of its shares. He also founded Ropart Asset Management, which his family completely owns. His son Todd, the managing partner of Ropart, is Blyth’s former head of mergers and acquisitions. Ropart Asset Management’s offices are inside Blyth’s headquarters. Todd’s brother Robert Jr. is the head of Blyth’s PartyLite unit and an outside adviser to Ropart. For good measure, their mother, Pamela Goergen, is a long-serving Blyth board member.

Ropart Asset Management owns more than 576,000 shares of Blyth, part of the 3.4 million shares controlled by the Goergen family.

The Goergens are hardly the only family to practice corner office nepotism and everything listed above has been disclosed in one filing or another. The conflicts of interest involved in the Goergens’ running ViSalus as an ATM for themselves are another matter.

When Blyth struck a deal in August 2008 to buy ViSalus in stages, the Goergen family used shareholder capital to buy out Ropart’s private investment in the firm at what Blair’s book indicates was 10 times forward earnings. So far the Ropart Asset Management Funds (and thus the Goergen family) have netted $15 million from the ongoing buyout. It is fair to wonder what — if any — incentives existed for Blyth to aggressively negotiate the sale price lower when Goergen family members were the sole beneficiaries.

Soon after the August 2008 deal, Goergen family members started landing board or executive roles at ViSalus, with Todd serving as chief strategy officer. It’s not unheard of for private equity executives to temporarily assume management roles in companies they invest in, but usually this is for the short term. They claim to be experts in managing assets, after all, not operations.

Todd Goergen’s situation illustrates just how lucrative wearing two hats can be. Todd has kept his Ropart job, while collecting a $500,000 annual salary as ViSalus’ chief strategy officer; he is eligible for a performance bonus of as much as $1 million. If an IPO is completed, Todd will receive 2.05 percent of the company’s shares in options and restricted stock.

The blurring of the lines between the Goergens’ personal investments and professional obligations seems to be by deliberate design, not accident, and part of their strategy for ViSalus. Ropart owns 4 percent of ViSalus and its funds charge ViSalus $8,500 a month for management services. The incentive for the Goergen family to complete an IPO is obvious: Based on Blyth’s $1 billion valuation of ViSalus, the shares held by Ropart should be worth at least $40 million, with Todd holding another $20 million stake. Whether the IPO happens is, of course, up to the market. In the meantime, family members are being paid while they wait; other Blyth shareholders are not.

Through Ropart, members of the Goergen family also own minority stakes in some of ViSalus’ key vendors. As of June, ViSalus had paid FragMob LLC $1.7 million in fees this year for services, including development of an app for mobile phones, as well as some credit card swipers, and $800,000 to iCentris, a maker of direct-selling software. Todd Goergen is a member of FragMob’s board and ViSalus’ founders own stakes in both these companies.

Credit the Goergens for their patience, though. When ViSalus stumbled some in 2009 and Blyth was forced to write down many of the assets in its investment to zero, it did not exercise its right to walk away from the deal. Only beginning in 2010 did ViSalus begin the growth that would prove such a double-edged sword.

Then again, the Goergens have direct experience with the darker side of network marketing companies. In 2006, shortly after putting cash into ViSalus, Ropart also took a stake in iMergent, a Utah-based software company cofounded by legendary stock promoter Shelly Singhal. (In 2010 Singhal was indicted for his role in a securities fraud; the charges were reduced to mail fraud last summer.)

From the minute Ropart made its investment, iMergent’s management was embroiled in a pitched battle with short sellers who derided iMergent’s software as worthless and its business model as that of a poorly disguised multilevel marketing company.

In keeping with the Blyth-Ropart-Goergen family tradition of interlocking ownership, Neal Goldman, a Blyth board member since 1991, was the largest holder of iMergent stock and its most vocal defender. He accused the short sellers of illegal tactics and fraudulent claims. Eventually the company sued short seller Andrew Left (a court tossed out the suit two years later with iMergent paying his legal fees).

Goldman probably should have kept his mouth shut. After numerous state attorneys general sued iMergent for making misleading claims, its CEO unceremoniously left the organization in 2008 when the board found he had violated disclosure rules. Then Todd Goergen took over the reins. The company moved its headquarters to Arizona, entered the Internet services business and changed its name to Crexendo. After the company’s stock price peaked at $29 a share in early 2007, the shares now trade at just a tad over $2.

Shake economic$

What the Goergens and Blyth are involved in with ViSalus is as conceptually different from Blyth’s neighborhood candle and potpourri parties as Pat Boone is from Motley Crüe.

The type of selling done for Blyth’s PartyLite unit is what a management expert might call “high touch,” since the emphasis is on social gatherings of friends and neighbors who personally view and sample the products. While the process is fruitful over the long haul, it can be time-consuming and imprecise. Someone attending an initial sales party might buy a single product and wait months or a year before really opening her wallet. Over time, though, that customer might host a sales party and bring in 20 new customers, a few of whom might organize additional parties.

The entry point for the ViSalus consumer experience is the Body by Vi challenge, a 90-day period during which a person picks a weight-loss goal and tries to achieve it using the Vi-Shape shake mix and supplements. Distributors — or “promoters” as they are called — are supposed to stage “challenge parties” to market the product.

ViSalus’ fast sales growth might seem to indicate that its products work. The truth isn’t so cut and dry.

The company claims to have engineered “millions of pounds lost” and prominently features online pictures of customers made sexier and slimmer from consuming its shakes.

But to evaluate the products’ true effectiveness, the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation asked two independent experts to examine ViSalus’ 90-day challenge and the ingredients of the Vi-Shape shake mix: Dr. Melina Jampolis, a nutrition specialist and author of “The Calendar Diet,” and dietician Keri Gans, author of the “Small Change Diet: 10 Steps to a Thinner, Healthier You.”

Gans was blunt. “Do they work? Absolutely [shakes] will help you lose weight over a 30-day period.” But she added, “They will absolutely guarantee you gain it all back, if not more.” Since ViSalus provides no instructions for how a person should modify his behavior and does not help introduce changes in how he relates to food (what to eat more of and what to consume less of), the old eating habits remain, Gans argued. Plus, the minute a person exits any shake plan, weight gain inevitably results, she said.

“When the weight comes back, it’s really devastating,” Gans said about shake diets in general and their users. “They simply give up and remain unhappy and unhealthy, or double down, with the same results. I’ve never seen shakes work for anyone wanting permanent weight change.”

Dr. Jampolis was more circumspect. “My concerns are more nutritional and about the marketing than the program,” she said. “Shakes are proven to be an effective first step as someone begins a permanent shift in approach to food. It’s not clear to me, however, that enough emphasis is placed on nutrition after the shake program ends.”

“The cost is much higher than it needs to be,” Dr. Jampolis added. “You could very easily make a much lower-priced shake with ground chia fiber, for instance, and other higher-quality ingredients.” (Diet products and vitamins are two staples of the multilevel marketing universe because they are inexpensive for a company to source and are often in high demand.)

The doctor is right that a Vi-Shape regimen is not cheap; 30 days’ worth of product in ViSalus’ Transformation Kit runs about $249. So figure that a three-month setup costs $750, not including shipping fees. (At least one enterprising ViSalus skeptic managed to put together a nutritionally similar shake for about two-thirds less per serving.)

The back-and-forth between shake opponents and supporters about the alleged nutritional value of ViSalus products is playing out on numerous websites. See the comments from readers here and here, as well as this video critique of ViSalus’ marketing presentation. Nonetheless, ViSalus makes a seductive appeal to consumer psychology: It sells a quick fix to a thorny problem on an installment plan. Skeptics are left to play the role of Cassandra, citing the stern medicine of long-term behavioral and lifestyle changes.

ViSalus asserts numerous claims about the remarkable scientific basis of the products behind its sales success. The company has spared no effort to brand its products as the nutritional heir to the meal-replacement shakes around in one form or other since the 1970s. Until the company updated its website after the name change to ViSalus Inc. from ViSalus Sciences, it declared, “Comprehensive research and development (R&D) is critical to the success of ViSalus’ products” and that it is “dedicated to bringing the best minds together with the best science to deliver cutting edge nutraceuticals.”

That’s a mighty tall order for a company whose scientific advisory board consists of just two people: Dr. Michael Seidman and Steven Witherly. ViSalus’ product development expenses of $1 million were paid entirely to Dr. Seidman for product royalties and consulting fees. He earns another $180,000 a year for appearances at promoter conferences.

And ViSalus conferences extol massive enthusiasm for anything to do with science. Dr. Seidman is regularly given a rock star’s welcome — replete with an entrance song — when he makes his jargon-dense presentations to ViSalus promoters about Vi-Pak, a vitamin and mineral supplement that he developed. Audience members, hanging on every word, eat it up. What they might not know, however, is, speaking skills aside, there is nothing very special about what Dr. Seidman does for ViSalus, according to the company’s filings: “We believe that the products covered by the [Seidman] license are replaceable in the event that the license is not renewed … and do not believe that … the non-renewal of the license would have a material impact on our results of operations and cash flows.”

Dr. Seidman is an ear, nose and throat specialist with an extensive research background in hearing loss. He frequently mentions that he holds several patents in his appearances before ViSalus distributors, but only one of his patents is for vitamins; the rest pertain to hearing loss. Dr. Seidman owns the Body Language Vitamin Co., serves as a staff hearing and throat surgeon for the Henry Ford Health System in West Bloomfield, Mich., acts as a paid endorser of an herbal remedy for tinnitus and edits several academic journals dealing with hearing loss. ViSalus prominently features a White Papers tab on its website, to proudly display a series of Dr. Seidman’s papers — mostly dealing with hearing loss.

Witherly is a nutritionist with a doctorate from Michigan State University. His career is more of a pure play at the intersection between nutraceuticals and direct sales; he has held research positions at Herbalife and a unit of Amway. He is now CEO of Technical Products Inc., a Valencia, Calif., consultancy that has advised companies whose formulations include supplements for erectile dysfunction and hangovers. Though Witherly generally has a lower profile within ViSalus, as a multilevel marketing veteran, he displays a level of enthusiasm and a hyped sales approach in his presentations in keeping with the concert-like aspect of promoter conferences.

That pyramid thing, for real

In the 1980s the Federal Trade Commission laid out guidelines for multilevel marketers concerning acceptable business practices. At a minimum, they have to move away from “inventory loading” (obligating distributors to buy a certain amount of product each month) and have retail sales operations, through which distributors sell to a public customer base, not just to one another.

Yet as long as multilevel marketers have described their compensation structure in a way that addresses these issues, they have largely been left alone and can retain a pyramid structure. While trade and securities regulators have scrambled to bring about compliance — and have sent the occasional message — multilevel marketing companies have become legally sanctioned outposts within the American economy.

In its prospectus, ViSalus bluntly assured would-be investors that the company is not running a pyramid scheme, but an analysis of the details of its operation as explained on its website and in the prospectus suggests an entirely separate reality.

ViSalus directly addressed the pyramid structure issue in the prospectus as follows: “Our individual promoters are paid by commissions based on sales of our products and services to bona fide purchasers, and for this and other reasons we do not believe that we are subject to laws regulating pyramid schemes.” ViSalus also pointed out that its distributors are not required to buy products monthly.

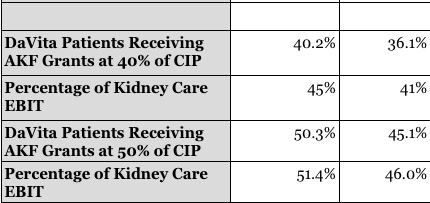

Written this way, ViSalus is in the clear. And, to be fair, consumer sales account for 66 percent of ViSalus’ revenue, with distributors’ purchases making up for the rest. Yet the company’s prospectus shows that on average for the first six months of this year the typical customer spent $240 versus $1,286 by distributors. This seems odd if ViSalus is claiming its distributors are not required to buy products.

Most ViSalus’ kits for promoters come with individual sample packets to give to prospective clients, so a promoter would have no reason to hold any inventory beyond a personal supply. Moreover, company filings say products are shipped directly to a customer. It’s hard to conclude anything other than that promoters are buying product to improve their sales performance or to maintain their perks.

While ViSalus’ promoters do not have to buy a fixed monthly allotment of products, they do spend money — often a lot. Corporate policy requires every promoter to buy at least a $49 “basic” membership, essentially providing a packet of marketing materials and three shake samples. Yet ViSalus’ entire marketing and training program is geared toward directing promoters toward buying one of two options: a $499 Executive Success System package, with promotional materials, videos and free samples, or a $999 offering, basically two Executive Success System packages.

Without the Executive Success System package, according to ViSalus materials, promoters cannot participate in a weekly revenue sharing pool and the ViSalus Bimmer Club. (For those in the Bimmer Club, ViSalus pays $600 toward the lease of a ViSalus-branded black BMW, as long as the promoter’s sales network brings in $12,500 a month in revenue; if sales fall under that figure, the lease becomes the promoter’s obligation.)

In other words, good luck to distributors trying to get ahead at ViSalus without shelling out at least $499.

ViSalus further emphasizes in its prospectus its pyramid avoidance through its manner of sales compensation, stating unequivocally that ViSalus pays “individual promoters commissions based on product sales, not recruiting.”

Narrowly cast, this is correct: A promoter can earn a commission for selling a single bag of shake mix to a customer. But a close read of ViSalus’ compensation plan makes it very clear that life as a ViSalus promoter is built on recruiting additional promoters.

If a promoter sells to a consumer, he earns a commission of at least 10 percent that can rise to 25 percent, based on the order’s dollar volume. To earn a respectable living, he would have to sign up customers multiple times a day, every day of the year, with few of them dropping out. Selling a $249 Transformation Kit, for example, brings in slightly less than $25 in commission.

But if a promoter immediately turns new buyers into promoters and builds a network right away, the income can potentially skyrocket. When a promoter adds three customers to her network, she receives a month’s supply of product. If this is done within her first 30 days of joining the Body by Vi Challenge, she becomes eligible for a whole new tier of rewards called Rising Star: a share of the weekly enrollers’ commission pool (2 percent of ViSalus’ sales). But she must also enroll three other promoters during those first 30 days with a minimum of $2,000 in total product sales.

See how ViSalus tries to have its cake and eat it too? Its filings meet the letter of the law by allowing a participant to earn some money selling to a customer but the spirit of all its programs is clear: Bigger payoffs come from immediately turning a customer into a promoter who is part of an actively expanding network.

In a video posted to YouTube of another ViSalus national sales training seminar this past summer in Miami, Sarnicola underscores the underlying goal to a room full of promoters who have achieved the vaunted status of director: “So I want you guys to make a distinction here between what the marketing message is and what the business model is. The marketing message is ‘challenge, challenge, challenge.’ But once you’ve got somebody in as a promoter, it’s ‘director, director, director.’” No elaboration here about nutrition or the process of weight loss.

Yet, being a ViSalus distributor is a risky proposition. Though the company does not disclose the dropout or “churn” rate for promoters, the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation pieced together this rate from annual filings and the prospectus: 197.1 percent for last year. This year through June, on an annualized basis, the churn rate was 194.2 percent. (In contrast, Herbalife, whose churn rate has been a major headache for its company, has about a 51 percent turnover among its distributor ranks.)

Perhaps ViSalus’ high churn rate can be explained by additional Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation analysis from data disclosed in the prospectus: This year through June, the typical distributor for ViSalus bought on average $1,286 in products but earned only $1,638 in commissions, netting $352.

Promoter churn becomes even more significant because it appears that ViSalus is able to count recently dropped-out promoters in its much touted customer total, which it claimed was as high as 1,058,000 in June. Read the fine print below to see how this is possible.

ViSalus defines a customer as “[a]nyone who has purchased products from us at least once in the previous 12 months, other than any purchaser who qualifies as an individual promoter on the measurement date.” Under that definition, ViSalus could include its customer tally promoters who bought items within the past year but who are no longer active and so can’t be considered “individual promoters.” That’s because ViSalus defines an “individual promoter” as a “person eligible to receive a commission within the ViSalus promoter compensation plan on the measurement date.” And to qualify for a commission, a promoter must have booked $125 or more in monthly automatically shipped sales.

So if one assumes the (very) conservative estimate of about 150,000 promoter dropouts in the past year, ViSalus’ 1,058,000 customer figure — more than 1 out of every 300 U.S. residents — is greatly inflated by the inclusion of promoters who are no longer active.

Waning health

Blyth’s third quarter 10-Q document filed Nov. 7 shows it is a company in poor health, with every page of the filing indicating that the subsidiary is propping up the corporate parent.

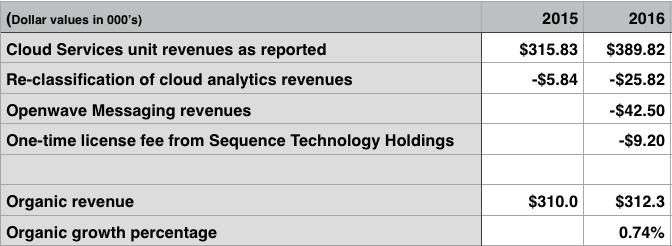

Most important, Blyth’s liquidity situation is becoming dire, according to this chart, whose figures were culled from the recent filing. With $85.4 million of 5.5 percent bonds due in November 2013 against $80.2 million in readily accessible cash, the company has reached panic button time. Fortunately for Blyth, it was able to sell its Sterno unit for $23.5 million last month to build its cash reserve back up to almost $103.8 million.

The sale of the Sterno unit is a good example of how ugly things have become for Blyth: As a profitable unit entering its busiest part of the year, Sterno is the type of division any healthy company would ordinarily hold onto.

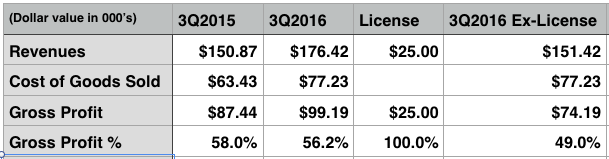

Blyth’s non-ViSalus businesses remain in free fall, with sales dropping 16 percent in the third quarter, to just under $99 million. PartyLite’s revenue declined 21 percent, with the unit posting an operating loss of $10.7 million. (PartyLite’s big season is the holidays, so the fourth quarter may show improved sales.)

ViSalus is Blyth’s saving grace, bringing in $169.9 million in revenue for the quarter, a 132 percent increase from the same period the prior year. ViSalus earned $27.4 million for the first nine months of this year, allowing Blyth to turn a profit.

Which is why the Goergens should be feeling worse than ever.

ViSalus, the only thing standing between them and heartbreak, appears to be beginning to wind down its era of unprecedented growth. To be clear, ViSalus’ posting a 132 percent sales increase in the third quarter over the same period last year is remarkable, but the company looks a lot closer to Earth than it did when posting 451 percent revenue growth. Unlike PartyLite, diet product companies tend to do their worst in the fourth quarter.

On Nov. 7, for the first time, Visalus announced that its number of promoters shrank from the second quarter to the third, from 114,000 to 110,000. A few days later, on Nov. 12, ViSalus posted a video on YouTube, explaining how it is sharply increasing the cash rewards for promoters moving by March to the upper ranks of distributors. Increasing promoter commissions might help boost or stabilize sales, but it will definitely weigh on profits. And Blyth’s management needs every penny of ViSalus’ profit to make up for its own losses.

In another first, on Nov. 21, Blyth announced Visalus’ inaugural dividend payout — some $22 million in total, with almost $16 million going to Blyth. Naturally, the Goergens shared in the good fortune, with their Ropart fund collecting $880,000 for its 4 percent stake. Like the Sterno sale, this is another clear sign of weakening financial health: If the goal is to ultimately consolidate ViSalus into Blyth, paying taxes on a dividend makes little sense unless the cash is desperately needed. And no manager would pull capital out of a business growing at 100 percent or more annually to reinvest it in a shrinking business unless it was to stave off a collapse.

It would be interesting to hear what Blyth’s management, the Goergens and the crew at ViSalus have to say about all this, but they ignored all questions posed them by the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation. For the record, more than a dozen attempts were made via email, phone, Twitter and overnight mail to get someone at Blyth, ViSalus or Ropart to answer questions about liquidity, promoter churn and whether ViSalus is a pyramid scheme. (We even sent emails to Blyth’s outside legal counsel and its board of directors but received no reply.)

Blyth’s stock price is now about $15. Perhaps once investors saw the prospectus and examined the figures, they began to run. For those doing their homework, it’s easy to see why: epic churn, an unsustainable business model and a weak corporate parent that can’t readily make good on a deal to finish buying ViSalus.

The trio of Ryan Blair, Nick Sarnicola and Blake Mallen are slick opportunists who have built the latest infernal multilevel marketing machine, promising everything to the desperate and gullible, if only they buy in.

It will undoubtedly end badly for most, if not all, who rely on peddling shake powder. For ViSalus’ leaders sitting atop the pyramid in the Hollywood Hills and Miami, there’s plenty of cash on hand for now — until they figure out how to make their next fortune.

What no one saw back in 2008 was that it would end so badly for Blyth. Then again, with multilevel marketing — as in life itself — very few ever see the end coming.