Slowly but surely answers to the many riddles of how Insys Therapeutics could achieve its mercurial success are beginning to emerge.

The Scottsdale, Arizona-based pharmaceutical company has only one commercial offering, a sublingual Fentanyl formulation called Subsys, whose sales growth has managed to double its market’s size, to more than $500 million from an estimated $225 million since its approval and launch in March 2012, according to executives at rival companies. In turn, the upward march of the company’s share price has turned its growing legion of supportive brokerage analysts and money managers into minor geniuses. (Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation readers will recall Insys from an April 24 investigation of the drug’s mounting number of lethality cases and the company’s unusual marketing efforts.)

Therein lies the rub.

Subsys is approved only to treat breakthrough cancer pain. The market for such drugs was estimated to have an annual growth rate of about 10 percent in the spring of 2012, according to former Insys sales staff and rival pharmaceutical executives. Instead, on March 21, 2014, about two years after its launch, Subsys managed to nose past Cephalon’s Actiq, then a leader in this narrow category, in number of prescriptions written, according to IMS Health data obtained by SIRF; last September Subsys took the lead for good.

These opioid drugs are so potent that the Food and Drug Administration created a stringent prescription protocol for them (known as TIRF-REMS), with multiple steps for a patient to go through before a prescription is dispensed.

Yet according to Medicare Part D records for 2013, no oncologists appear on the list of Subsys’ biggest prescribers.

Given this apparent lack of support from oncologists, it appears odd that insurance companies seem to have embraced Subsys, continually approving its reimbursement at a level none of its competitors can obtain. A leading Subsys prescriber told the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation that in his estimation, “Insurers cover over 90 percent of [Subsys prescriptions] for at least one [90-day] cycle,” whereas rival drugs appear to have an approval rate hovering at 33 percent. The doctor’s account of a chasm between how insurers treat Subsys and how they deal with its rivals was corroborated by a senior executive at an Insys rival and three former Insys sales staff members.

But it was not until records in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments database were released in October 2014 — covering the last five months of 2013 — that a linkage could be more readily detected between the volume of Subsys prescriptions and payments to doctors.

As Insys’ share price continued to trend upward, Wall Street’s brokerages found it easy to promote the company’s business practices, as a Jefferies research report from December shows.

But now federal prosecutors are peeling back the veil to reveal a black world behind Insys’ earnings. The initial results suggest they do not condone what they are seeing.

————————

Dr. Gordon Freedman, a 55-year-old anesthesiologist, is in every way imaginable a member of New York’s medical establishment, with a busy two-office practice and, until very recently, a faculty appointment at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

A graduate of the Sackler School of Medicine, Dr. Freedman resides in Irvington, N.Y., a pretty village along the Hudson River just 20 miles north of Manhattan. This seems to be the perfect capstone to a life that outwardly evinces the virtues of taking initiative and pursuing hard work.

But in life, as in medicine, the mechanics of how the system works matter. And for Dr. Freedman, the road to success has been paved with lots of Insys’ cash.

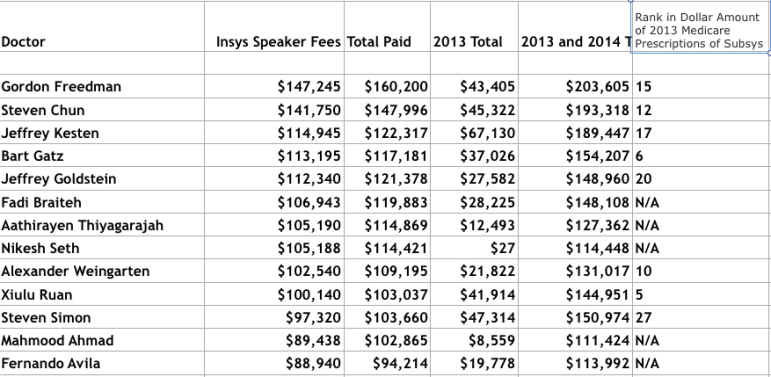

The June 30 update to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments database included the full amounts of pharmaceutical company payments in 2013 and 2014 to doctors for entertainment and speaking at corporate events and for research. The database revealed that in the last two years Insys spent almost $204,000 on Dr. Freedman, with more than $147,000 of that being for speaking programs last year in 52 separate payments of $2,400 to $3,750, not including food and travel expenses; none of the money was for research.

Was paying Dr. Freedman so much a good investment for Insys? Probably — at least initially.

Medicare Part D records show that in 2013, the most recent year for which data is available, Dr. Freedman ranked as the 15th-highest Subsys prescriber as measured by dollar amount, having written 35 prescriptions that cost Medicare $393,961. The Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation, via a database tracking TIRF-REMS prescriptions, identified 60 Subsys prescriptions that Freedman wrote from March 2012 (when Insys obtained FDA approval to sell the drug) to the end of December 2013.

The math behind a typical prescription shows why Insys has not been hesitant to pay prescribers to talk about the drug. In 2013 the wholesale acquisition cost of a 90-day supply of Subsys of 400 micrograms, statistically the most frequently prescribed amount according to Wolters Kluwers data, cost $4,608. In 2014 at a blended cost of $58.68 per unit (there was a midyear price hike), that same 90-day supply cost $5,281. Currently, priced at $97.80 per unit, a prescription costs $8,802. (These figures do not take into account frequent discounts.)

The Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation repeatedly reached out to Dr. Freedman to discuss his speaking engagements but he did not return multiple calls to his home, office or cell phone; he also did not reply to an email sent to his Mount Sinai address.

In response to questions about the ethics of Dr. Freedman’s Insys payments, Mount Sinai spokeswoman Elizabeth Dowling emailed the following statement: “Dr. Freedman is not employed by Mount Sinai and we do not have access to the details of his personal relationships with non-Mount Sinai entities.” She did not reply to follow-up questions.

As the chart below indicates, Dr. Freedman was hardly alone in profiting from Insys’ gravy train; 12 other doctors received more than $100,000 last year from the company.

The nearly $7,390,872 that Insys spent last year on payments for what it calls “compensation for services other than consulting” — with $6.3 million going to doctors and the almost $1.1 million balance for travel and entertainment costs — stands out from the practices of its competitors marketing TIRF-REMS drugs. The $7 million sum represents 7.2 percent of Insys’ 2014 selling, general and administrative expenses, with the speaker payments amounting to 2.9 percent of its total sales.

In comparison, Galena BioPharma, the maker of Subsys competitor Abstral, spent just $132,372 on what it calls “honoraria,” representing 0.4 percent of selling, general and administrative expenses, with speaker payments amounting to 0.8 percent of total sales. (To be fair, Depomed, the maker of Lazanda, spent $206,250, or 3 percent, of its almost $7 million in sales on speakers.)

When the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation interviewed Insys’ sales chief Alec Burlakoff in April, he bristled at the suggestion of a quid pro quo between prescription-writing volume and speakers program compensation. As he saw it, the speakers program was the pharmaceutical industry version of a university’s faculty lounge, where colleagues could discuss the latest approaches and innovations in their discipline (albeit one where the conversations are shaped by frequent payments of thousands of dollars, as opposed to a reinterpretation of Sylvia Plath).

“Putting board-certified doctors together, where one of them is explaining the benefits he or she is seeing” [from prescribing Subsys] was the key to the company’s remarkable sales growth, Burlakoff said.

But federal prosecutors have recently served notice that they are taking a very different view of Insys’ speakers program. In a pair of cases in Connecticut and Alabama, assistant U.S. attorneys have removed some of the basis for support of the company among brokerage and investors by definitively linking three of the most highest-volume Subsys prescribers to Insys’ payments of “bribes” and “kickbacks” in open court.

————————

In Hartford’s U.S. District Court on June 23, nurse practitioner Heather Alfonso of Derby, Connecticut, pleaded guilty to accepting $83,000 in bribes from a pharmaceutical company that were designed to influence the choice and amount of prescriptions she wrote. According to an account of the proceeding, the company was identified as Insys and the payments were made under its speakers program.

Apart from the connection of the speakers program to bribery, Alfonso’s surrender of her prescription-writing licenses means Insys loses another important prescription writer, in the latest round of the cat-and-mouse type contest between law enforcement and the high-volume writers of Class II opioids prescriptions. She was the 22nd-highest Subsys prescriber in 2013, according to Medicare Part D data, and ranked 25th in Tricare records in 2014.

Alfonso, in her plea, admitted to having been paid for her attendance at 70 separate speaker dinners, with the prosecutor describing them as either having no doctors or physician assistants in attendance — and thus no educational value — or as meals with only her Insys sales representative and friends in attendance.

The plea completes a remarkably tumultuous six-year span for Alfonso. In July 2009, with five children and her parents claimed as dependents, she sued for protection from creditors under Chapter 7 of the bankruptcy code, listing $424,682 in assets and $525,316 in liabilities.

According to Alfonso’s plea agreement, she is potentially facing 46 to 57 months in prison but the prosecutors reserve the right to request that a judge adjust that figure, presumably downward. None too subtly, this means that Alfonso has a remarkable incentive to negatively portray Insys and its sales practices.

Reading between the lines of the press release announcing Alfonso’s plea, however, an observer could infer that federal prosecutors are expanding the investigation beyond the bribery plea into insurance fraud.

“Interviews with several of Alfonso’s patients, who are Medicare Part D beneficiaries and who were prescribed the drug, revealed that most of them did not have cancer, but were taking the drug to treat their chronic pain,” according to the release. “Medicare and most private insurers will not pay for the drug unless the patient has an active cancer diagnosis and an explanation that the drug is needed to manage the patient’s cancer pain.”

To whit: Alfonso’s patients received Subsys despite the absence of a cancer diagnosis; without it, a refusal of coverage is nearly automatic within the field. Thus the granting of insurance reimbursement could imply that somehow the diagnosis codes of these patients were changed.

This also speaks to what the unnamed physician referenced above, about Subsys prescriptions’ being approved by major commercial insurance carriers and Medicare much more frequently than prescriptions of rival medications were.

On investor conference calls, Insys CEO Michael Babich has mentioned a dedicated prior authorization unit that works closely with a prescriber’s office and sales staff to assist with paperwork. But other rivals do this, too, and while Insys might realize more efficiencies, it seems unlikely that the company is almost three times better at this.

One possible answer is provided in a class action (recently settled for an undisclosed amount): A confidential witness from Insys’ prior authorization unit claimed that staff people were trained to impersonate prescriber office staff when talking to pharmacy benefit-management companies, lie about the previous drugs taken by the patient (most insurers require patients try a generic drug and have it fail before a branded drug is approved) and tailor diagnoses to insurers, based on internal records of prior approval rates.

Insys never responded to these charges prior to the class action’s settlement.

Another possible explanation lies with the remarkably close working relationship that Insys has with a drug distributor called Linden Care, based in Syosset, New York. Former sales executives describe this bond as much closer than the standard vendor-distributor relationship, such that any issue with a prescription could be rapidly cleared up and, despite the multiple checks and balances within TIRF-REMS, the drug appear at the patient’s door within 24 to 48 hours. Linden Care has recently been put up for sale by its owner, BelHealth Investment Partners. A phone call to Inder Tellur at BelHealth was not returned.

————————

Alfonso’s legal predicament pales in scope next to the May charges filed against two pain-management physicians, Dr. John Couch and Dr. Xiuliu Ruan, partners in Physician’s Pain Specialists of Alabama in Mobile. Ranking as No. 3 and No. 6, respectively, as prolific Subsys prescribers through Medicare, in 2013, and second and first as Tricare prescribers for 2014, the pair had almost certainly become the company’s largest single revenue source.

With the two doctors arrested and charged with conspiracy to commit health care fraud and for distributing controlled substances, prosecutors released a few weeks ago a pair of affidavits that the Federal Bureau of Investigation special agents who led the investigation had filed.

Both agents described a veritable Class II drug prescription-writing factory, with prescriptions being written every four minutes and almost no medical analysis occurring from the harried physician assistants who saw the majority of the clinic’s patients. Undercover agents posing as patients with demonstrably false injury claims were barely examined yet received multimonth subscriptions for Class II drugs.

FBI Special Agent Amy White said that a confidential informant employed by Dr. Couch and Dr. Ruan described their participation in a pharmaceutical company’s speakers program as being “paid for promotion.” (While Insys was not named specifically, thc company’s identity can be deduced given the amount and timing of the payments cited.)

Similar to Alfonso’s case, the Insys speakers program is portrayed in the FBI agents’ affidavits as little more than Dr. Couch’s and Dr. Ruan’s being paid thousands of dollars for having dinner with their sales representative, according to the confidential informant. (A former Insys sales representative told the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation that Dr. Couch and Dr. Ruan have been personally close for a decade to their Insys representative, Joe Rowan, whom they also dealt with at Teva Pharmaceuticals.)

Agent White’s affidavit alludes to the possibility that Dr. Couch abused the same class of drugs he so frequently prescribed. In a joint operation with a county drug task force, the FBI obtained the content of the trash from Dr. Couch’s residence and found that several syringe and Subsys packages had been discarded. Additionally, a confidential witness told the FBI of observing used syringes in the restroom of Dr. Couch’s personal office. Dr. Couch has a history of alcohol and prescription drug abuse, per his testimony in a California Medical Board account of the probationary certificate he was awarded in 1995, while completing a one-year pain-management residency at UCLA.

Another FBI special agent, Michael Burt, said he estimated that 50 percent to 60 percent of the clinic’s gross proceeds were derived from fraudulent activities. He said payments from Insys were found in several personal bank accounts of Dr. Couch and Dr. Ruan that he sought to seize. Another account of Dr. Ruan, Burt said, contained “kickbacks” from Industrial Pharmacy Management, a drug distributor whose founder Michael Drobot pled guilty in February 2014 to a $500 million insurance fraud scheme.

The Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation sought comment from Dr. Couch and Dr. Ruan. Neither doctor replied to multiple attempts to obtain comment.

Dennis Knizely, Dr. Ruan’s defense counsel, did respond, however, saying his client has been unfairly targeted: “These are baseless accusations, centered on the government’s interpretation [of complex issues] only. We will fight this at trial and show the government to be wrong.”

Added Knizely: “Dr. Ruan’s patients had many medical problems, including cancer, serious auto and work-related injuries. I have no doubt insurance companies have a problem with him; he ordered specific and complex procedures done to ensure the best care for his patients. His medical decisions will be shown to be sound and compassionate.”

John Beck, Dr. Couch’s lawyer, did not return multiple calls seeking comment.

————————

One of the odder elements in Insys’ operations has been its relationship with key sales executives. In April the company sued two salespeople, Lance Clark and former Western region sales chief Sunrise Lee, for purportedly maintaining outside jobs. The company has since amended its claim against Clark but dropped the suit against Lee. A call to Clark was not returned; an inquiry to Lee was referred to her lawyer, Stephanie Fleischman Cherny, who did not respond to a request for comment.

In addition, on May 8 Insys sued Michael Ferraro, a sales representative covering southwest Connecticut for maintaining an outside interest in a compounding pharmacy. On May 28 Ferraro filed a response, claiming that he had fully disclosed his interest in the pharmacy, that he was winding it up and that he had notified the company of a series of what he alleged were federal violations stemming from an April 17 lunch with his district supervisor, Michelle Breitenbach. On July 10 Insys dropped its suit against Ferraro.

Prior to the July 4 holiday weekend, Insys dismissed Fernando L. Serrano, Dr. Freedman’s sales representative. Serrano’s LinkedIn profile mentions a stint at JPMorgan Chase as a mortgage banker but not a 2012 stint at two heavily sanctioned boiler rooms, Aegis Capital and John Thomas Financial (a firm expelled from the securities industry by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority in 2015, along with its founder). Serrano told the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation that he was still in shock about his Insys dismissal.

A former Insys sales executive said that the large amounts of Subsys prescriptions written by Dr. Freedman and other prescribers that Serrano had called on in 2014 had propelled him into the top-tier of revenue generators.

Serrano declined to elaborate upon why he left Insys, other than saying, “It’s just insane” several times. A follow-up call was referred to his lawyer, Ali Benchakroun, who declined to comment.

An email to Insys sales chief Alec Burlakoff and New York regional sales manager Jeff Pearlman seeking comment about the reasons for Serrano’s dismissmal were not returned.

The Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation left a voice message for Insys CEO Michael Babich and sent an email with a series of questions. He did not reply.

Additionally voice messages and emails (when addresses could be found) were sent to the top 10 doctor recipients of Insys payments in 2014 but none responded.