Executives at Insys Therapeutics have continued to pressure its employees to develop new ways to mislead insurance companies into granting coverage to patients prescribed its drug Subsys, even as the Food and Drug Administration’s Office of Criminal Investigations is issuing a stream of subpoenas to former employees.

As reported in a December Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation story, Insys’ prior authorization unit (also known internally as the insurance reimbursement center) employees were trained and rewarded for saying anything, including purportedly inventing patient diagnoses, to get Subsys approved. The revelations illuminated the answer to the conundrum raised in our previous stories: How does a company marketing a standard fentanyl spray formulation, under a strict FDA usage protocol, easily double the insurance approval rates of its more established competitors?

Internal Insys documents and an audio recording of a prior authorization unit meeting show that as recently as the late autumn executives were frantically brainstorming new ways to get around increasingly stringent pharmacy benefit manager rule enforcement.

“[Pharmacy benefit managers] had begun to deny Insys’ [prior authorization] requests in the early autumn to the point where it was rare to get more than two dozen approvals per week for the unit,” said ex-prior authorization staffer Jana Montgomery (a pseudonym) and something that began to accelerate after the CNBC reports came out.

“That’s a big change from each employee getting 25, at least, per week.”

Unlike their sales unit colleagues, Insys prior authorization staffers can’t call on long standing professional relationships with prescribers or use speakers program cash to win business. They are hourly workers — albeit among the higher paid prior authorization staff in the medical industry — dealing with other hourly workers and both have little latitude to depart from established scripts. If the pharmacy benefit manager denies the coverage, Insys has few levers to pull, apart from beginning an appeals process.

As critical reports began to pile up in the press, particularly a November CNBC investigative series — and with at least a half-dozen state and two concurrent federal investigations ongoing — insurers began to deny authorization for Subsys.

By the spring Montgomery said that it was clear to everyone in the unit that something had to change or the business would grind to a halt. One big problem was that insurers appear to have gotten wise to what was known internally as “the spiel,” a script of dubious answers to pharmacy benefit manager employee questions designed to clearly suggest the patient had been diagnosed with breakthrough cancer pain (while not coming right out and saying so).

Put bluntly, with state and federal subpoenas becoming a common occurrence, the prior authorization unit could no longer afford to push the legal limits of word games. On the other hand, simply reporting an off-label diagnosis was an unpalatable option given that under 3% of Insys’ patients had cancer.

So Jeff Kobos, the prior authorization unit’s new supervisor, wrote a new version of the spiel that was alternately called “Statement 13” or, in a homage to its confidential nature, “Agent 14.” It tried to thread a needle, designed to navigate both elevated pharmacy benefit manager scrutiny and the rising level of compliance oversight required, while still allowing the unit’s employees to try and guide pharmacy benefit managers to an approval.

The problem being, according to Montgomery, is that the prior authorization unit had gotten behind the curve.

“If you’re doing a prior authorization it should always be straight forward and exactly what the provider gives you,” she said. Pharmacy benefit managers “learned to approach [Insys] with questions that had non-negotiable answers like, ‘On what date did the patient receive their original cancer diagnosis?’

“We didn’t figure that out right away and kept on submitting requests for authorization which were all quickly rejected.”

So like many corporate outfits the world over, the prior authorization unit held a meeting to discuss how to get better results (where “better results” was defined as getting people to think patients with back or leg pain had cancer.)

The Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation obtained a recording of this meeting, held in November.

The initial speaker (and the clearest voice) is prior authorization executive Jeff Kobos who makes a pair of important admissions: At the 2:20 mark he acknowledged the unit’s pattern of dishonesty by saying “when we were using [insurance codes for cancer-related pain diagnoses] for non-cancer [pain].” At 4:30, he made jokes referring to “sandwiches” and “the sky is blue” as the kind of conversational gambits they should try to deflect pharmacy benefit manager worker questions with.

At 5:00, David Richardson a trainer with the prior authorization unit, suggests dropping the “Agent 14” spiel since it wasn’t working. A minute later, he and his wife, Tamara Kalmykova, an analyst with the prior authorization unit, begin to discuss an idea he had in response to so-called smart-scripting, whereby employees of a pharmacy benefit manager use software analysis to determine if a patient — per the FDA’s protocol — had tried another fentanyl drug.

(Montgomery said smart-scripting was another development that Insys’ prior authorization staff couldn’t readily steer around.)

Richardson suggested patients use a coupon for a free-trial prescription of Cephalon’s Actiq. The patient wouldn’t pick the drug up but it would register in databases and allow prior authorization staffers to plausibly claim that the patient was in full compliance with regulations.

But smart-scripting wasn’t the only new obstacle that unit staffers were encountering. Humana, Silverscripts Medicare and other pharmacy benefit managers started requiring not only Actiq or Depomed’s Lazanda, a nasal spray, but the previous use of other major painkillers like morphine, oxycodone and hydromorphone. Still others were calling prescriber offices and confirming every aspect of the diagnosis, including prior history with fentanyl and other opioids.

Adding in a variable like the delivery system (lozenges, nasal spray or inhaler) did offer Insys an opportunity to claim that its patients could only tolerate oral inhalers. Montgomery said pharmacy benefit manager questions about prior use of Lazanda, for instance, were handled by noting the “provider states patient cannot tolerate inter-nasal spray.”

Unfortunately for Insys’ shareholders, the hard line taken with its prior authorization unit is having a very real effect on prescription count, according to IMS Health data.

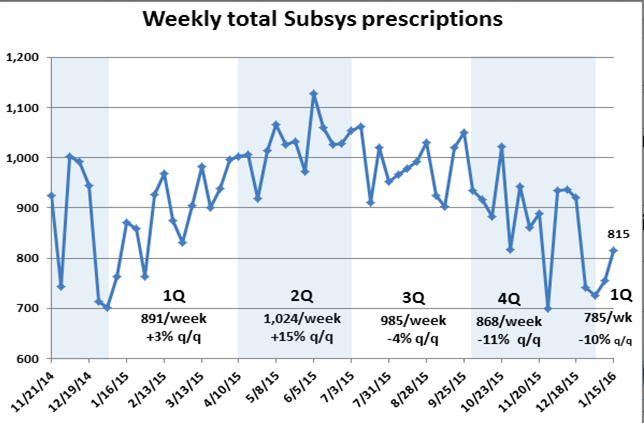

The number of Subsys prescriptions filled in the third quarter dropped about 4 percent from second quarter levels and the erosion accelerated in the fourth quarter, falling an additional 11%.

Thus far in January, the new year has not brought much in the way of promise, with the 815 prescriptions reported for the week ended Jan. 15 down 6 percent from the comparable week a year ago. Subsys’ share of the transmucosal immediate release Fentanyl market, which hovered near 50 percent for most of the summer, has now fallen below 45 percent.

————————

Jana Montgomery was given a pseudonym because of her cooperation with an ongoing federal investigation. Her account of prior authorization unit practices was read to two of her former co-workers who agreed with her characterization of “the spiel” and declining pharmacy benefit manager authorizations.

As is the case with prior Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation investigations, everyone named in the story was called repeatedly on mobile or home phones and left detailed messages about what we sought comment for. When possible an email was sent as well. As of publication, no one replied.

A detailed message was left on Insys general counsel Franc Del Fosse’s mobile phone seeking comment on these subjects. As of press time the call had not been returned.