If someone wanted to use a Venn diagram to illustrate what is wrong with the U.S. health care system, picking the different sets would be easy: Price gouging, abuse of loopholes, hidden risks to patients, baffling regulatory decisions, marginal efficacies and the use of doctor payments to stimulate drug sales would be some logical choices.

And a case in point would be Corcept Therapeutics, a specialty pharmaceutical company based in Menlo Park, California, and the apparent union of all things expensive and opaque. So how did Corcept, a small company with just one drug aimed at treating a tiny population of patients with a rare pituitary disorder, wind up there?

Corcept has managed to make handsome profits by quietly yet efficiently exploiting gaps in the nation’s health care regulatory framework. And its sole drug is none other than the storied mifepristone, better known as the abortion pill. While Roussel-Uclaf developed mifepristone in France in 1980, it became famous in the U.S. in 2000 when the Food and Drug Administration ruled that doctors could prescribe it to induce an abortion; it was sold as RU-486.

Just before that, two doctors at Stanford University Medical School’s psychiatry department began examining mifepristone for quite another use. In the mid-1990s Dr. Joseph Belanoff began testing a longstanding hypothesis of then-department chairman Dr. Alan Schatzberg that mifepristone could block the body’s production of cortisol and be used to help treat episodic psychosis, a condition that’s found in about 15 percent of people with major depressive disorder.

Encouraged by the results they observed in the few patients they tested, the doctors founded Corcept in 1998, with Stanford University’s technology licensing office serving as a silent third partner; the university had applied for a patent covering mifepristone’s use in treating depression.

The doctors proved adept at generating national interest for Corcept’s early-stage trial: Dr. Schatzberg proclaimed in 2002 that the drug’s potential was “the equivalent of shock treatments in a pill.”

But a preliminary study of mifepristone, released in the journal Biological Psychiatry in 2002, kicked off the academic equivalent of a food fight when several veteran psychiatric researchers argued that the test results provided no statistical backing for Schatzberg’s claims. One high-profile critic told the San Jose Mercury News in 2006 that the study was an “experimercial,” or an experiment whose purpose was to generate publicity rather than meaningful results.

These critics were onto something: In 2007 Corcept halted its clinical trial for the drug’s treatment of depression and did not publish the results, a development that usually means that the findings were not positive.

Faced with the prospect of the company’s business model collapsing, Corcept’s management managed to pull off what an April 2018 Kaiser Health News article called a “Hail Mary” when it sought — and received — Food and Drug Administration approval to test mifepristone as an orphan drug for the treatment of Cushing’s syndrome.

Endogenous Cushing’s syndrome is a pituitary gland disorder whereby the body is prompted to make too much adrenocorticotropic hormone, which governs the level of cortisol. And people with hypercortisolism — who overproduce cortisol — might have their metabolic functions go awry; this could lead to a host of painful and dangerous symptoms like rapid weight gain, skin discoloration, bone loss, heart disease and diabetes.

The primary culprit behind endogenous Cushing’s syndrome is a tumor that grows on the pituitary gland; in 70 percent to 90 percent of these cases, surgery to remove the tumor can successfully address the condition, according to the Pituitary Society.

But for as many as 30 percent or so of the people with Cushing’s syndrome (individuals who can’t undergo surgery or for whom surgery doesn’t mitigate these symptoms), Corcept developed a mifepristone treatment. And on Feb. 17, 2012, the FDA approved Corcept’s application to market its mifepristone medication Korlym as an orphan drug. The label, or the official designation for what it was approved to treat, is very specific: Korlym is to be prescribed only to people with endogenous Cushing’s syndrome who have both hypercortisolism and diabetes in order to reduce side effects of hyperglycemia, or high blood sugar levels.

The fact that the FDA had granted an approval allowing the company to market Korlym, however, doesn’t mean Corcept had scientifically demonstrated the drug’s success in treating Cushing’s syndrome.

Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation readers may recall from previous reporting on Acadia Pharmaceuticals that the FDA can sharply relax evidentiary standards when confronted with a small patient population possessing a rare disease.

Indeed, the FDA approved Korlym based on a single open-label study consisting of one group of 50 patients. (An open-label study is the least rigorous type of scientific investigation.) All participants in the study knew they were receiving the drug — and not a placebo — which risked the possible introduction of bias. And the study lacked a comparison group, whose results could be contrasted with those of the drug’s recipients. Plus, 36 of the 50 study participants reported protocol violations.

The FDA’s risk assessment and risk mitigation review for this study did conclude that Korlym’s trial design was flawed without the testing of an approved comparator drug, but “the progressive and serious nature of [Cushing’s syndrome] would make it unethical to randomize any patients to placebo.”

When the company tried to expand Korlym’s sales by seeking approval to market it in Europe, other problems emerged. In March 2015 Corcept withdrew its application for Corluxin (a renamed Korlym) after receiving a final round of questions from a committee of the European Medicines Agency and declining to answer them; the company cited “strategic business reasons” for ending the process.

In a late December 2018 interview, Corcept’s CFO Charles Robb told the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation that the reason the company pulled Corluxin’s application was “primarily commercial.”

Robb said, “We just at the end of the day couldn’t figure how we would make any money [in Europe] selling it, given the way they priced [orphan] drugs.”

The European Medicines Agency had a starkly different view of events. In a brief “question and answers” release posted online in May 2015, the agency’s committee said its “provisional opinion” was against approving the drug. Three weeks later in a more formal assessment, it cited a laundry list of concerns, including the company’s failure to control the introduction of impurities during manufacturing, the design of the clinical trial and “limited” evidence of effectiveness.

Robb did not respond to a follow-up call and email with questions from the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation about why Corcept spent the time and money to pursue approval of its drug all the way to the last stage of the process before realizing it couldn’t make money in Europe.

Asked about the recent sharp increase in the number of deaths recorded for Korlym in the FDA’s adverse events reporting system (FAERS), to 37 in the first nine months of 2018 from 17 for all of 2017, Robb was adamant that none of the deaths could be directly attributed to Korlym. In response to a question about how he could be certain of that, he said, “All [the FAERS death reports] are adjudicated by a third party”: Robb added that Corcept retains Ashfield to provide pharmacovigilance, a service that evaluates reports of a drug’s adverse events for a manufacturer. And he insisted that the medicine and its dosage were not responsible for any of 103 deaths reported for Korlym since 2012. He did not answer a question about why 17 of the 103 death reports mentioned “product used for unknown indication.”

A brief aside: Adverse event reports are a tabulation of patient responses to a drug. The reports are unverified and are not designed to replace a formal investigation or autopsy. This completely voluntary reporting system allows for a wide array of filers, and with family members, caregivers and trained medical professionals able to make submissions, the level of accuracy and detail varies widely. Finally, many medical professionals have suggested that because this documentation is voluntary, incidents involving newer drugs are not reported to FAERS.

(To present a more nuanced view of patient deaths on Korlym, the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation obtained longer form FAERS reports via the Freedom of Information Act. While not official reports, they do provide valuable context and data, such as dosage, basic health datapoints, initial diagnosis and the duration of Korlym use. Accordingly, any instances where the circumstances of a patient’s death suggested that a reaction to Korlym was secondary were eliminated.)

Ashfield officials did not return a call seeking comment.

Robb did, however, have a lengthy list of possible causes for these deaths: “The thing to understand is these patients are very ill. Some of them have adrenal cancer,” he said, “Some of them ahead have been suffering from the symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome for decades; some are simply elderly and the list of medications these patients have to take can be 20 and 30 drugs long.”

————————

Nonetheless, as Corcept’s recent income statements show, the company has certainly figured out a way to make quite a bit of money in the United States from selling this drug. Corcept’s road to success in this country has followed the tried and true specialty pharmaceutical playbook, raising a medication’s price steeply and often, while using physician speakers bureau payments to build drug awareness.

The public battering of other specialty pharmaceutical company CEOs after they tried to defend price increases might have given Corcept’s Dr. Belanoff the idea of acknowledging unpleasant facts first — before others do. Thus in April 2018 Dr. Belanoff told Kaiser Health News, “We have an expensive drug, there’s no getting around that,” perhaps in an effort to diffuse some of the sticker shock of his drug’s price tag, which he later cited as $180,000.

But that’s not anywhere close to a person’s cost for a year’s worth of Korlym prescriptions. Dr. Belanoff’s quote is only for the annual price for prescriptions of 300 milligrams, which is half the suggested 600-milligram daily dose. A more accurate yearly cost would be $308,000. And the annual expense for a patient will probably rise since, as Dr. Belanoff noted in a recent conference call, Corcept expects the typical prescription to eventually be 730 milligrams daily, the dosage explored in the FDA study.

Taxpayers are playing a growing role in Corcept’s expansion plans. According to Medicare Part D coverage data, in 2016 (the most recent year for which statistics are available), the government forked out $23.1 million for 1,086 prescriptions in the United States, a steep increase from 2015’s $11.4 million expenditure. All told, Medicare Part D payments accounted for just slightly more than 28 percent of Corcept’s revenue in 2016, a jump from 14 percent in 2015.

Medicare Part D and the Department of Veteran Affairs records are the only two sources for the general public to search for details about who prescribes Korlym. People who rely on private insurers place their orders through a single specialty pharmacy, whose sales are not reported to prescription-monitoring services. According to Medicare Part D payment records, 44 doctors each wrote at least 11 Korlym prescriptions in 2016. (The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services doesn’t release the names of doctors writing 10 or fewer prescriptions.)

Eleven of the 15 doctors who are the most frequent prescribers of Korlym to Medicare Part D enrollees received at least $7,500 in speakers bureau payments from Corcept in 2016 and 2017 combined. (The centers’ Open Payments Data portal lists payments only to medical doctors and not physician assistants; its data for 2018 will be released in May, along with 2017 Medicare Part D data for Korlym.)

A savvy observer might suspect that Corcept is using its speakers bureau program to compensate doctors for prescribing Korlym.

To be sure, the concept of a speakers bureau is a fully legal, well-used strategy employed by many pharmaceutical companies. Done by the book, these programs serve both marketing and educational purposes: Doctors are compensated for their time in preparing presentations and discussing their experiences of administering a medication to their patients, and other physicians can hear a discussion about the drug at a level of sophistication that a sales representative would be hard pressed to match.

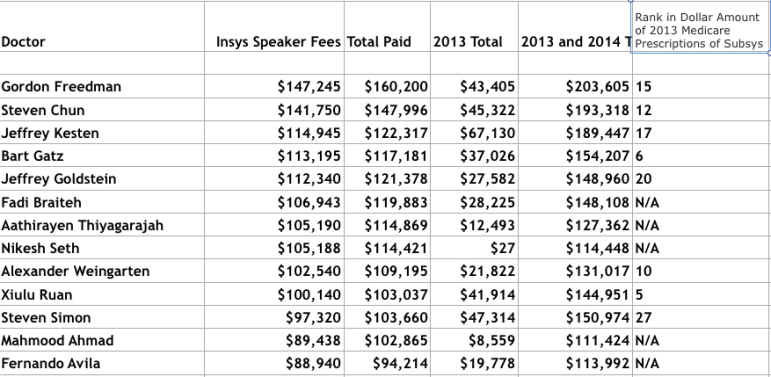

But in practice, as the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation found after its investigation of Insys Therapeutics, speakers bureau programs (if not carefully monitored) can devolve into frequently questionable, if not illegal, quid pro quo inducements.

Another thing that stands out in the list of high-volume Korlym prescribers is their peculiar geographic clustering. Cushing’s syndrome is a rare disease. The FDA has estimated that the number of people in the United States who could be prescribed this drug is 5,000. So some medical experts might be surprised to see Korlym prescribers found mainly in small towns and modest-sized cities, many at a substantial distance from established medical research centers. (For example, Dr. John C. Parker, a Wilmington, North Carolina–based endocrinologist, wrote at least 41 Korlym prescriptions in 2016. But one would have expected instead that some larger-volume prescribers would be located, say, in the state’s heavier populated Durham and Chapel Hill area, where two pituitary disorder clinics are affiliated with prominent university hospitals. Wilmington, though, is about 2.5 hours by car from these clinics.)

Could these doctors based in smaller communities with a limited pool of patients to draw from be prescribing Corcept to patients merely with diabetes — instead of endogenous Cushing’s syndrome?

When Corcept’s CFO Robb was asked during the late December interview if his company was using its speakers bureau program to encourage doctors to prescribe the drug for off-label uses, he said the company was doing no such thing. He argued that the FDA’s estimate of 5,000 U.S. patients who could potentially take the drug was somewhat arbitrary and nearly seven years old. He said that a better figure, based on research by Corcept and Novartis, is closer to 20,000. (Novartis is in the late stages of testing its own Cushing’s syndrome drug.)

In addition, Robb said that as awareness of Korlym grows, doctors will realize that more of their patients have Cushing’s syndrome, and the clustering of Korlym prescribers in smaller communities happened only because one group of physicians recognized earlier than their colleagues how the disease could be treated.

Pressed on the unusual odds of so many prescriptions for a treatment of such a rare disease from doctors in Zanesville, Ohio and Murfreesboro, Tennessee, Robb declared that “over 90 percent” of all Korlym prescriptions were “on label.” He added that “since it’s an expensive drug,” nearly all commercial insurers have an extensive preapproval process before paying for the drug.

Speaking more generally about Corcept’s marketing efforts, Robb said a company has a lot of work to do when selling a medicine for a rare disease like Cushing’s syndrome. “It is just not the case that you can walk into a doctor’s office, drop off some brochures and come back later and suddenly they’ve got a Cushing’s syndrome patient. It takes five to seven visits” for physicians to become aware of the disease, he said.

“I know the meal [served during the presentation] is modest,” Robb added. “It’s held at your local Holiday Inn or whatever and it’s entirely compliant with the PhRMA code.” The code he referred to is a set of voluntary ethical guidelines for drug companies adopted in 2002 by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, frowning on sales representatives using gifts to doctors or providing them meals or entertainment as a means of drumming up business.

“We’re not flying people to Hawaii to hear about our drug,” Robb said.

Robb’s full-throated defense of Corcept’s business practices would make more sense if not for the company’s relationship with Dr. Hanford Yau. An endocrinologist, Dr. Yau sees patients at an Orlando Veterans Administration Medical Center’s clinic.

According to records obtained by the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation, Yau and his colleagues at the VA clinic prescribed Korlym for 84 people from early 2016 to Sept. 1, 2018. Yau wrote 27 of the prescriptions. A back of the envelope calculation, using 2017’s sales and prescription volume, illustrates how important the clinic is to Corcept: VA records from that year reveal that 50 people began taking Korlym through prescriptions written by the clinic’s doctors. With their medication costing the then-prevailing price of $290,304 a year (or $24,192 a month), these 50 patients generated more than $14.51 million in sales, or 9.1 percent, of the company’s $159.2 million in 2017 revenue. (Of course, some of those taking the drug in 2017 might have started only in the middle of the year. And the figure excludes patients who had already begun taking Korlym in previous years and stayed on the drug.)

Moreover, just as his clinic had become so central to Corcept’s economic well-being, Dr. Yau became the company’s leading recipient of speakers bureau payments. In 2017 he received $95,139 from the company — over 12 percent of Corcept’s total payments to medical professionals — a more than sevenfold increase from 2016’s $13,524, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Open Payment Data portal. (But in 2014 and 2015 combined, Yau was paid just $4,610.) The second leading recipient of the company’s speakers bureau cash in 2017 was Dr. Joseph Mathews of Summerville, South Carolina, who was paid $73,777.

None of these payments were for research purposes, according to the Open Payments Data portal. Nor does Dr. Yau’s name surface on ClinicalTrials.gov, the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s database of public and private clinical studies.

Asked several times about this doctor’s relationship to his company, CFO Robb would speak only in broad terms about the speakers bureau program’s goals without discussing Dr. Yau. He did not answer a follow-up question sent via email. And Dr. Yau did not reply to a phone message or email.

Through a Freedom of Information Act request, the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation obtained emails between Dr. Yau and Corcept that show he was working with an Italian endocrinologist and another VA colleague to create a white paper for marketing Korlym to “community physicians.”

The expectation for a peer-reviewed medical journal article is that an investigator’s research is conducted independently from consultations with a drug’s manufacturer. But the emails obtained through the FOIA request, as shown in the image below, show that Corcept was entirely in control of this project conceptually and editorially. (The image also reveals where the VA redacted the name of the person directing the project for Corcept and other related identifiers.)

In addition, the fact that the Orlando VA Medical Center generates so many Korlym prescriptions is rather curious. The patient base of the VA’s medical system nationwide has in recent years been more than 91 percent male, according to the department’s analysis of those using its services from 2006 to 2015. But Cushing’s syndrome typically occurs in women rather than men, by an almost 5-to-1 ratio, according to the National Organization of Rare Disorders.

Susan Carter, a VA spokeswoman, did not reply to several calls and an email seeking clarification about Dr. Yau’s prescribing of Korlym and compensation for serving as part of Corlym’s speakers bureau.

Update: This story has been amended to include two paragraphs discussing the natural limitations of the FDA’s Adverse Events Reporting System and the Southern Investigation Reporting Foundation’s approach to reporting with this data.